I am a Reader in Physics at Glasgow University, leading a team of researchers embedded within the wider Imaging Concepts Group which consists of four academic PIs. My research team develops novel optical microscopy techniques, with a particular interest in the intersection of light sheet microscopy, computational imaging, and in vivo biology. Live organisms and cells are often moving (on various length scales), and much of our research is directed at overcoming problems caused by that motion, or developing better ways to measure it when the motion itself is of scientific interest. A key highlight of my recent research is my development of heartbeat-synchronized imaging to enable long-term timelapse imaging in the beating heart itself.

Some of the research questions and challenges I am currently interested in include:

- Can we make imaging systems sufficiently motion-tolerant to permit advanced techniques such as structured illumination microscopy and 3D deconvolution in vivo in the beating heart?

- Can our imaging and flow measurement tools help unravel the biomechanical coupling between heart structure, flow and electrophysiology?

- How do we support as many labs as possible to access our advanced motion-stabilisation technologies?

- How can we best exploit the relationship between information, measurements and imaging?

- How can we rethink the imaging & analysis pipeline, improving it by building in knowledge of physical models and expectation at an early stage?

- What application possibilities are opened up by fast widefield fluorescence lifetime imaging camera technologies (which we have early access to)?

Outside work, I enjoy spend my time exploring the mountains of Scotland on foot, and rock climbing. I am a volunteer member of Lomond Mountain Rescue Team, assisting lost, ill or injured walkers and climbers in the nearby mountains.

Motion-stabilised imaging

Research into organ-level development and function is confounded by motion artefacts, originating from the heartbeat, breathing motion, and pulsatile blood vessels. All of these issues prevent high-resolution 3D imaging and dramatically degrade the effective resolution of image sequences. Most microscope imaging techniques require serial plane-by-plane acquisition, and if the sample is moving then the sequence of planes will not represent a self-consistent snapshot representation of the sample. For example, when imaging the beating heart, one plane might be acquired in systole and another in diastole.

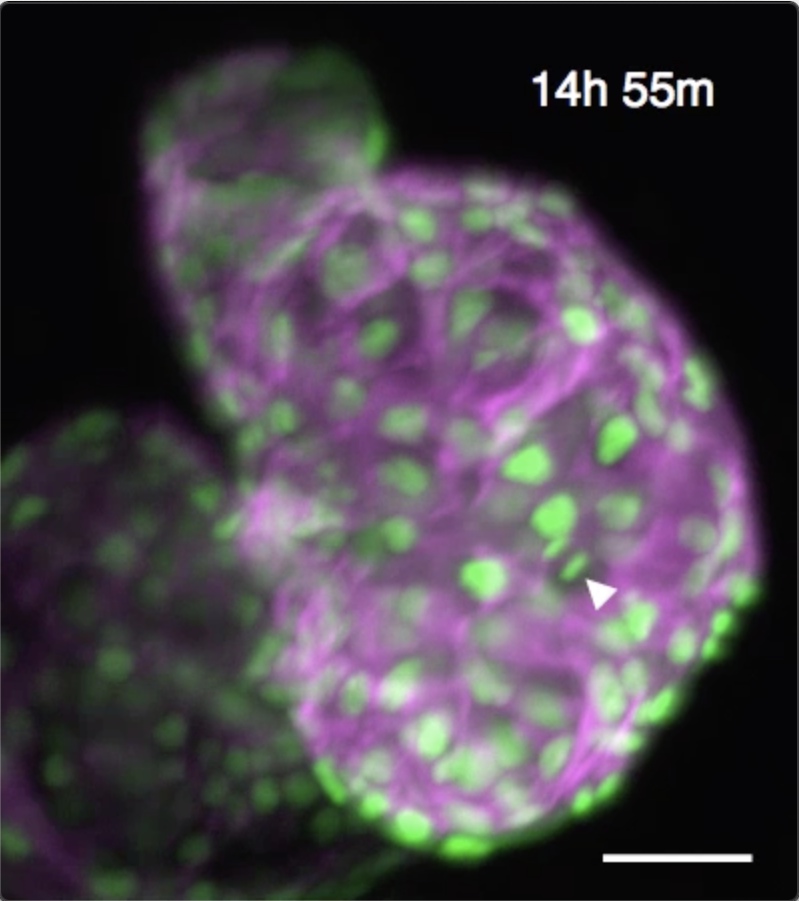

We have developed techniques to computationally “freeze” periodic motion such as the heartbeat, enabling us to acquire high-resolution 3D snapshot images of the unperturbed beating zebrafish heart. By developing algorithms to maintain that “phase lock” even in the face of dramatic developmental changes, we are able to sustain time-lapse imaging for 24 hours or more. This unlocks huge potential for biomedical research in the heart. Several recent publications have been driven by this unique ability to directly witness dynamic cellular processes within the beating heart. These have included the cellular migrations driving trabeculation, understanding immune response to injury and the role of macrophages in cardiac regeneration.

More background on the biomedical motivations behind our work can be found in this British Heart Foundation supporters article.

We are now seeking to maximise access to our heartbeat-synchronization technology, both through a mix of collaborations with individual research labs and through ongoing collaborations with several microscope companies.

Measurement-driven approaches to eliminate imaging artefacts

Some imaging techniques such as light field microscopy suffer from severe artefacts under certain circumstances, and other techniques using exotic point spread functions rely on deconvolution to recover a sharp image from raw data that does not resemble a conventional image. What if we could actually exploit those artefacts, in conjunction with the motion in the sample being imaged, to learn more about the motion and recover an improved image? We are developing new techniques to do this, by considering the whole imaging and analysis pipeline from acquisition all the way through to image-based measurements. Benefits include improved velocimetry, reduction of light field microscopy artefacts, and the potential to solve the problems of bias that plague brightfield-based particle image velocimetry. A sneak peek of this research in progress can be found here

Taking this measurement-driven approach to its extreme, can we take the camera out of the loop entirely? Can we make sophisticated image-based decisions even in scenarios where we have nowhere near enough information to reconstruct an image from our measurements? The answer is yes!

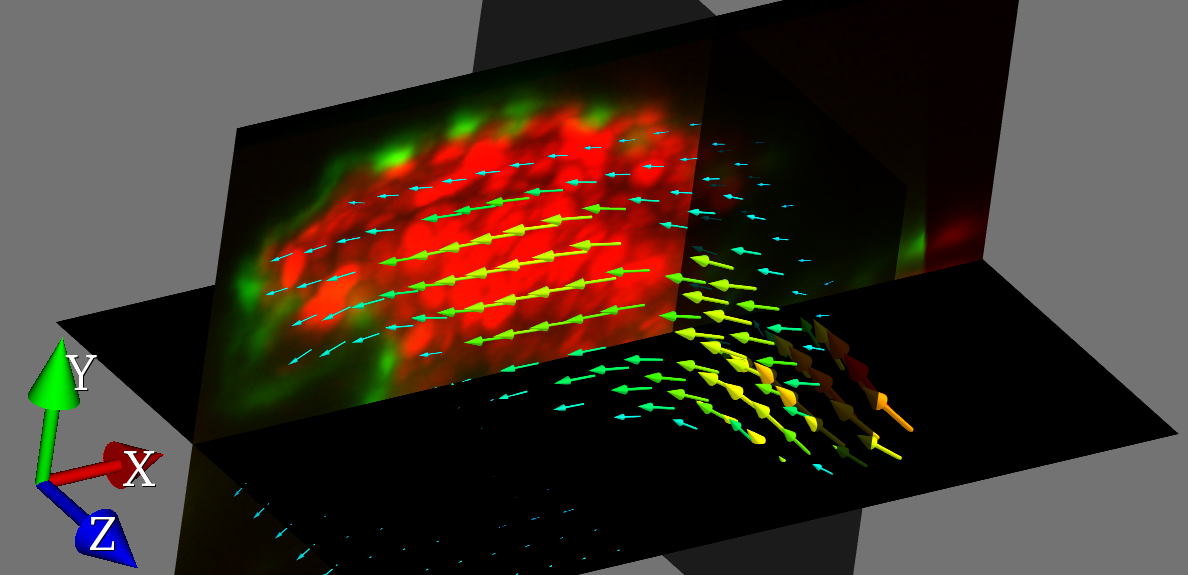

Quantitative flow field measurement

Taking inspiration from particle image velocimetry (PIV) as used in aerospace engineering, we have combined PIV with light sheet microscopy to achieve 3D-resolved flow imaging of the zebrafish circulatory system. We can map out the flow fields within the zebrafish heart with milisecond and micrometer precision, using the blood cells themselves as tracers. A key innovation was to use our heartbeat-synchronization techniques to permit correlation averaging of data collected over multiple heartbeats, enabling us to build up low-noise flow fields from very noisy and sparse raw data.

Snapshot volume imaging

What if we could acquire an entire 3D volume image of a microscope sample from just a single 2D camera image? Our ongoing research into new mathematical frameworks for 3D image recovery is showing great promise for reconstructing extended objects including filament structures, blood vessel networks, and cellular organelles. Our ability to image a volume in a snapshot sidesteps limitations on volume acquisition rates in fluorescence microscope, opening up new possibilities for 3D imaging of fast dynamic processes.

Fast, widefield fluorescence lifetime imaging

Fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) is traditionally achieved using point-scanning microscopy techniques. Exciting new lifetime imaging camera devices have huge potential for fast widefield imaging, but scanned fluorescence imaging techniques (particularly two-photon microscopy) are poorly matched to the characteristics of a widefield FLIM camera. We are developing new optical approaches (more results in the pipeline - coming soon!) to enable fast, efficient two-photon FLIM. Further work is ongoing to tackle the challenges of imaging deeper into dynamic living tissue.

Smart microscopy

A theme running through several of these research areas is that of smart microscopy, in which realtime computational analysis drives decisions about when to image, what to image, and even realtime feedback and manipulation of the sample. Other examples of our work in this area include contact-free hydrodynamic confinement and manipulation of microparticles, precision heartbeat-synchronized laser ablation in the beating heart and foveated imaging that dynamically adapts the camera’s attention to important objects in a scene.